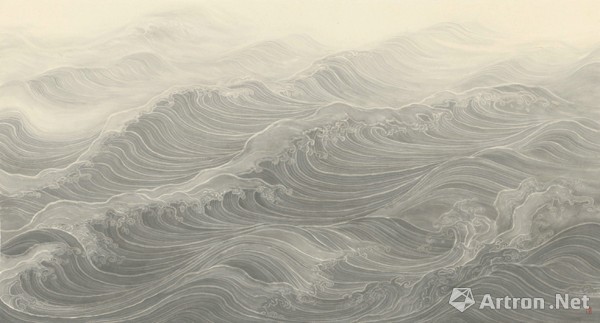

王牧羽将马远《水图》转化为自己的作品时,冒了很大的风险——可能会被人理解为食古不化的“抄袭者”。因为,他用了几近苛刻的标准“再现”马远。怎样苛刻?对比两人作品,我们会发现水纹的细节形态几乎一致。也许有人会说,长于临摹的中国画中,这不算什么。可问题的关键是,王牧羽“再现”马远的方法并非惯常的临摹技艺。他没有用线条“临摹”水纹,而是利用水墨在宣纸上的“自然晕化”呈现了马远的“水”。这是一项有着技术难度的工作。

Wang Muyuu took great risk of criticised as a copycat insistent on old patterns when he attempted to reproduce "Water Image", a painting by the Southern Song artist Ma Yuan. He held himself to the strictest standards to "reproduce" the original. For example, an examination of the original and reproduced paintings reveals that the water waves in them are almost the same. Some may say that it is not a great feat, since there are many precise reproductions of traditional Chinese paintings. But Wang stands out for his unusual techniques. Instead of using lines to reproduce the waves, he utilizes the natural halo effect of rice paper to render the imagery of water, which is a demanding job in itself.

众所周知,水墨具有一种独特的品性:借助宣纸对水的反应,笔痕周边会显现特殊的“边缘线”——墨色与空白之间的隔离与过渡。这种因材料而产生的“特殊反应”在中国画中很常见。但它却难于控制,通常是以随机的状态出现在画面中。王牧羽的工作难度正在此,他试图控制这种不可控的视觉要素。从某种角度看,这是在完成一种不太可能的“可能”。确实,画面中随机留下“边缘线”是一件简单且自由的事。但将自由的“晕化”变成一种可控的造型语言,极具挑战。

As we know, Chinese ink possesses a unique quality. When employed with water on rice paper, the ink leaves special lines on the edge of brushstrokes, which indicate the distinction and transition between the brushstrokes and the blank space. This effect is widely utilized in traditional Chinese paintings. But it is difficult to control the lines which often appear in a random manner. On the contrary, Wang Muyuu tries to take control over the randomly produced visual factor. In some sense, he is accomplishing the impossible "possibility". Indeed, these lines can be freely and easily produced in painting, but it is a great challenge to manage their formation and turn them into controllable modeling language.

这或许也是王牧羽敢于“抄袭”马远的原因。显然,“技术难度”在画家看来是一种能力的宣言,告知观者自己并非平庸之辈。王牧羽的“自信”似乎很见效,即便知道他的水图与马远有关,却没有人认为他在“抄袭”。这是一个有趣的现象,几乎一致的图像却直观地“否决”了抄袭。为什么?就观者而言,即便不知道这一技艺的表现难度,画面直观的视觉体验完全不同。马远的画面是线条流动的古典美学,王牧羽却是墨色延展出的洋气——调性丰富的高级灰。也就是说,王牧羽为马远提供了全新的“美学方案”,隐含了今天人们能够理解的视觉感受。

That may explain why the artist ventured to "plagiarize" the painting of Ma Yuan. Obviously, "technical difficulty" is, to an artist, a declaration of ability, declaring that he is not a mediocrity. Wang Muyuu's confidence in his skills has worked well, because no one really sees him as a copycat, although his work is closely related to the ancient painting. This is an interesting phenomenon: how could an exact reproduction not be seen as a copycat product? For audiences who have no idea of the technical challenges, they know that these two paintings deliver totally different visual experience. The original painting is in the classic aesthetical tradition that features rhythmically flowing lines, but Wang's adopted a modern style, as seen in the color of gray of varied tones. Put differently, the artist provides an aesthetic approach to the ancient painting in way that render it more accessible visual experience to modern audiences.

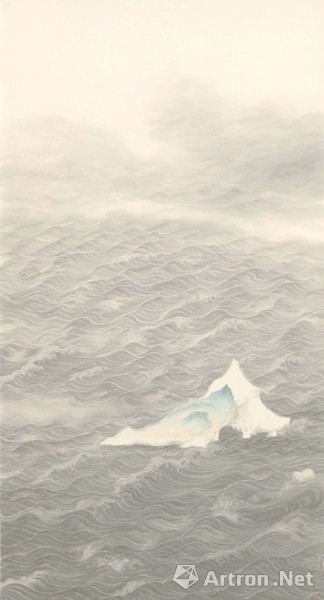

但这不是王牧羽的目标——让人们体验不同于马远的“美”。他的野心是将看似古典的图像经验转化为当下思考的载体。选择马远《水图》,隐含了新一代画家对“绘画”这一传统行为的重新审视。绘画,通常被认为是对物的虚拟再现,是“画——物”二元结构下的认知对象。但王牧羽却试图检讨这种历史悠久的认知经验,将绘画转变为“物——物”结构。这听上去有些玄奥,其实并不难理解。具体到王牧羽作品,与马远最大的区别就是表达水纹的“线条”。直观而言,两者显现为一黑一白——背后隐藏了完全不同的视觉逻辑。马远的线条是“笔墨”,是人描述世界的一种视觉语言;王牧羽的线条是“水痕”,是水因物理特性在宣纸上自动生成的痕迹。前者的“水”,是人工语言再现自然之水的“画——物”结构;后者的“水”,是自然之水自我生成的“物——物”结构。

But this is not the goal of the artist to help the audience appreciate a different beauty of the original painting; his ambition is to render seemingly classical visual experience into a carrier of modern ideas. And by choosing the Water Image, the artist reveals his reexamination of traditional painting behavior from the perspective of a new generation of painters. Painting behavior, is often seen as suppositional reproduction of objects and the cognitive target in the binary frame of "painting-object". But Wang tries to reconsider this old-age cognitive experience and turn painting behavior into "object-object" frame. This may sound abstract, but in fact it is quite easy to understand. If we read carefully Wang's painting, we see that its biggest difference with the original work lies in the lines of the water waves: they are of different colors – the former is white and the latter black. Behind them are different visual logics. In the original work, Ma Yuan adopted "bi'mo", which is a visual language widely used to describe nature, and in contrast, Wang Muyuu's lines are traces that water leaves on the rice paper – they are a result of the physical property of the paper. The "water" in the original work is a "painting-object" frame of reproducing nature by human, and Wang's "water" is an "object-object" frame of producing water by water itself.

从“画——物”到“物——物”,王牧羽巧妙利用水与宣纸的特性重构了马远的“水”,并因此反思绘画的传统观察方式。对王牧羽而言,马远的“线条”是“人的语言”对“自然之物”的翻译,而他的“水痕”却是将“人的语言”译回为“自然之物”,将绘画的“生产权力”最大可能地交还给物本身。这是一次有趣的“翻译”,绘画被置于“物对人的表达权力的反抗”中。虽然水痕的“被显现”仍然存在人的介入,但相对主观线条的肆意塑造,王牧羽极大释放了自然之水的话语权。整个创作过程,画家必须面对水在宣纸上的“自我”,绘画不再是人的完全表达,而成为人与物达成“妥协”的博弈过程。这是一种从来没有出现过的“绘画方式”:被描绘的对象以自身物理属性参与到画面的生产中。画家,不再是控制画面的“全能上帝”,而成为与描绘对象不断“协商”的参与者。

From "painting-object" to "object-object" frame, Wang Muyuu wisely leverages water and the physical property of rice paper to reconstruct Ma Yuan's "water", and at the same time, reexamines approaches to natural elements in traditional paintings. For him, while Ma Yuan's lines are to interpret natural elements in human language, his water traces are to translate human language into natural elements and allow objects to play the biggest possible role in art production. This is an interesting process in which paintings are put in object's resistance against the expression of human artists. Although the water traces are intentionally produced by the artist, natural water are given a greater say in producing the imagery of water, compared with artist's randomly produced subjective lines. In drawing the painting, the artist must face "the self of water" on the rice paper, because painting is no longer a free expression of his feelings – it has turned into a process of compromise between humanity and objects. This is an unprecedented approach to painting. The object painted participates in the production process with its physical properties. Painter is no longer "the Mighty God" controlling his painting, but a participant who needs to negotiate with the object painted.

在此,画家的主体权力遭遇了空前质疑。显然,这种带有“权力结构检讨”的思想转向,非常符合全球化语境中的后现代思潮。但是,对王牧羽而言这并非只是受益于西方话语。作为水墨材料的运用者,他似乎更注重中国传统中一些不为画家重视的思想。诸如老子的“以身观身”,至庄子《秋水》被明确为“以物观物”,即在观察、体认世界的过程中去除“人为”,正所谓“以物观物,性也;以我观物,情也”。剔除“我”而进入的世界,正是物自身的世界。这一源于东方朴素的、思辨的体悟,在王牧羽手中与西方不断“去主体”化的哲学反思获得了联姻,并最终显现为“以水为水”的画面营造。

Naturally, the dominant role of the painter is greatly challenged. And this idealistic shift containing the examination of power structure is in line with the post-modern trend in global context. But for Wang Muyuu, it does not benefit from western discourse alone. As a water-and-ink painter, he focuses more on some traditional thoughts often neglected by painters, included are Lao Tzu's idea that the public should observe themselves from the perspective of their own cultivation as well as Chuang Tzu's ides that to observe objects from the perspective of objects. Human factors need to be eliminated in observing and understanding the objects in the world, because from the perspective of the objects, we can better understand their nature, and from the perspective of humanity, we can only express our feelings and emotions. A world free from human factors are a world of pure objects. This simple Chinese argument is connected with western "desubjectivation" trend in Wang's painting, as evidenced by the water waves presented by water traces.

或许,正是发现了贯穿古今中西的理论空间,王牧羽才大胆而冒险地“抄袭”马远,甚至将“抄袭”对象放大为所有画过水的画家。然而,历史上单纯描绘水的画家极为罕见。水,通常是画面的组成之一,与山石、林木构成经典的山水图式。那么,面对多出来的山石、林木,王牧羽该如何处理?显然,继续“以物为物”的逻辑是困难的。用传统画法画出来,是一个选项。确实,王牧羽也这么做过。但这种方法干扰了“以水为水”的视觉特征,作品的视觉结构不再那么“单纯的极致”。面对难题,王牧羽再次冒险,将画中山石、林木表现为由水环抱的“空白”。

Probably became he discovers the theoretical link that connects western and Chinese, ancient and modern ideas, the artist has decided adventurously to "copy" the painting of Ma Yuan and in a large sense, all the painters of water. But there are few painters in history focused on water alone. Water is one of the elements in composition and forms classical landscape painting together with mountains and forests. In that way, how can the artist reproduce mountains and forests? It is obviously difficult to reproduce them with his "object-object" frame, while painting them with traditional techniques is an option. Indeed, Wang has done in this way. But this approach disturbs the visual character of the water waves, and reduces the pure visual structure of the entire piece. In response, he took another risk by rendering the mountains and forests into emptiness surrounded by the waters.

空白,意味着悬置,也意味着放弃——放弃画家主观描绘的权力。这种做法,不仅呼应了“以水为水”对于画家权力的质疑,而且还构建了类似反转片的效果,使“水图”在丰富的物象中继续保持“单纯的极致”。显然,“被放弃描绘的物象”在画中并未消失。它们以更醒目的方式出现在画面,仿佛一种视觉隐喻:“无需画家描绘的对象”以缺失的方式存在于绘画。毫无疑问,这是令人“意外”的视觉感受。无论语言抑或图像,绘画因此而不再是封闭的再现系统。相反,它承载着极为开放的意义空间,在东方与西方间、感官与思辨间来回游走。而这,是传统水墨无法带来的。

The emptiness means a compromise or forgoing of the painter's right to subjective drawing. This approach is a response to the challenges posed by the technique of drawing water with water, and creates an effect similar with reversal film in ways that ensure the "simple acme of perfection" of the waves. It is apparent that "the objects abandoned" does not disappear from the painting. In fact, they are present in a more conspicuous manner, just like a visual metaphor. In contrast, "the objects that the painter does not have to draw" are present in a way of absence in the painting. Undoubtedly, this is a surprising visual experience. From language to imagery, painting is no longer a closed process of reproduction. It now contains a meaning that is open to debate and moves between eastern and western ideas and between the sense and the mind. This is a function that traditional water-and-ink paintings can not fulfill.

2018年12月10日

December 10, 2018

Copyright Reserved 2000-2025 雅昌艺术网 版权所有

增值电信业务经营许可证(粤)B2-20030053广播电视制作经营许可证(粤)字第717号企业法人营业执照

京公网安备 11011302000792号粤ICP备17056390号-4信息网络传播视听节目许可证1909402号互联网域名注册证书中国互联网举报中心

京公网安备 11011302000792号粤ICP备17056390号-4信息网络传播视听节目许可证1909402号互联网域名注册证书中国互联网举报中心

网络文化经营许可证粤网文[2018]3670-1221号网络出版服务许可证(总)网出证(粤)字第021号出版物经营许可证可信网站验证服务证书2012040503023850号